Cocky-locky got away. I have no idea how. They can fly a bit, though, so maybe he flapped himself up ten feet and hid in a tree.

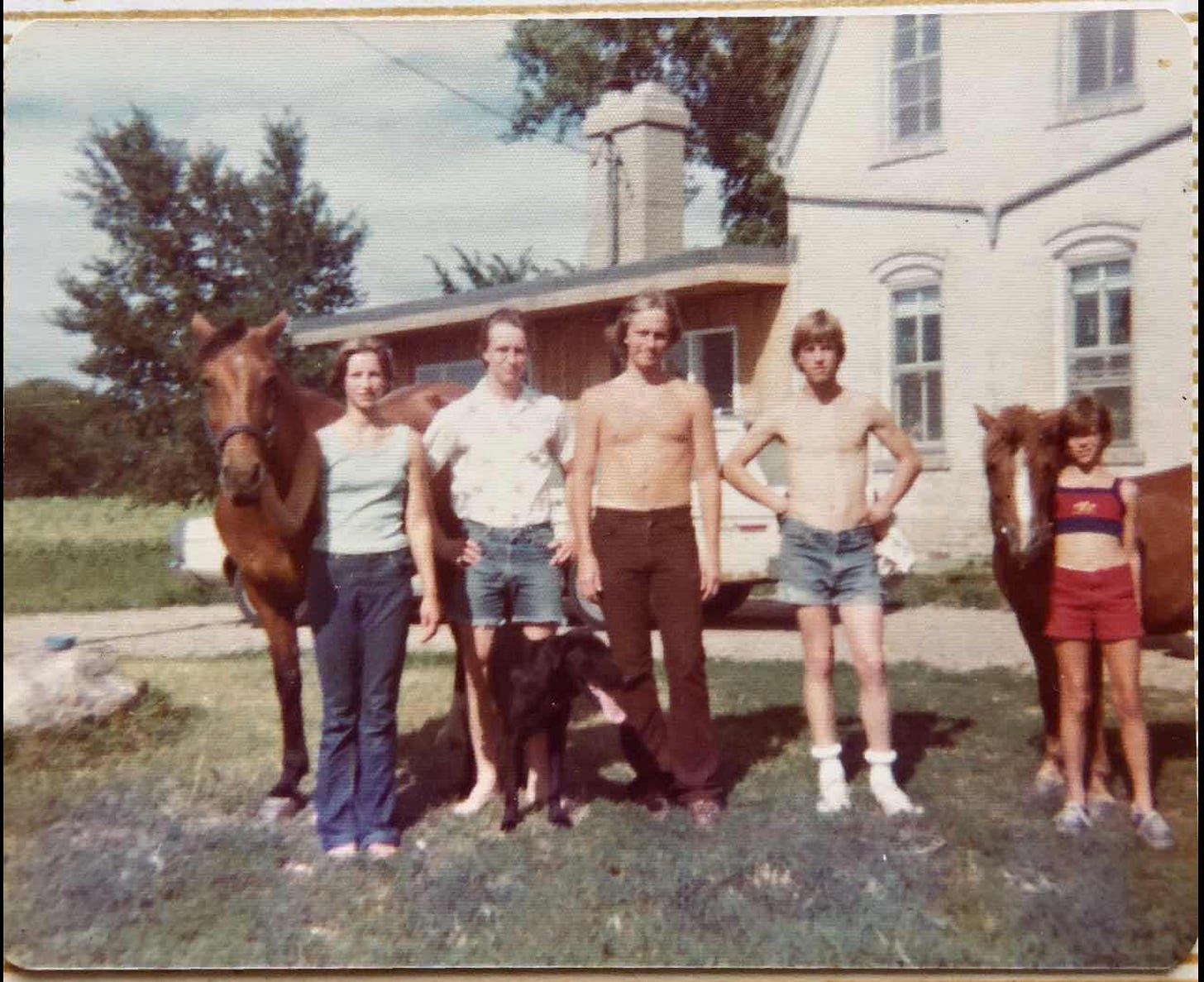

All 45 other chickens in late summer, the weekend after Labor Day, somewhere around 1977 at our farm in Chaska, Minnesota, got the hatchet, the steam pot to loosen their feathers, the plucking by me and my grossed-out brothers, and the gutting in the sink by Mom and our sisters.

Last I saw him — hold up, the first I saw him was early winter on our open front porch. He was squatting out there, occasionally arranging himself to be more fluffy. I think he had an infection in his butt, and we didn’t do any vet work on dumb chickens, although this one, having had the pluck or luck, survived by virtue perhaps of hiding himself away while the chopping was going on, in another part of the commandeered calf barn made into a chicken coop. The last I saw him, Cocky-Locky was pecking at pebbles along the quarter-mile driveway out to 212 in summer of 1978.

[Keep in mind: half of this hokum is made up or inflated off the actual-factual truth, and only fixable by my two sisters who lived there with me. Older brothers had already grown and flown from Minneapolis before the farm move. The other half, I swear, is true. An extra half is inspired, suppressed, untold, imagined, and finagled.]

“Dad, look! One got away. We missed one!” I said, around Thanksgiving. “Don’t look through the window, come on out, come on out and see! He’s ours, int he?” Various other comments came up like, “What, we gonna kill him now, too?” — followed by our mom hollering, “Goodness no! I have not got the stink of death out of the kitchen since then!”

So we pile out onto the open front porch and take a look at Cocky-Locky, lone ranger, the sneaky bastard who slipped the hatchet.

We’re all admiring Cocky’s miraculous self, and saying, “How’d he get away?” “Where was he?” “You missed him, Teddy!” “No, I got them all out of the coop, I swear to .. Pete.” “How many did we butcher?” “44.” “Then he’s number 45.” “No, we butchered 45.” “Then he’s number 46.” “How many we lose all summer?” “Couple died in the box.” “Yeah, but Dad, how many did you buy? That’s the only way to —” “Somewhere around there, 45.”

We decided he deserved to live, not that we fed him. He was on his own. Truce — he pecked my shins enough times while I fed him, and drew blood, we called it even with Cocky. My sisters will vouch. If it wasn’t him pecking our shins, then he could live with the guilt of his brothers and sisters pecking our sweaty, chicken dropping-dusted legs. I wasn’t killing any more of them. Nor would I protect him from our outside dogs.

I’d seen a lot of death, including dogs getting chickens, and if Cocky Locky was to get nabbed by Barney, Andy, or Ginger, well, sorry! no extreme measures now.

We’d had to shoot our buffalo bull when he got too horny horning the buffalo heifers in their sides so that they rammed through our barbed-wire fencing, and then we had to chase them all over the Minnesota River bottoms. We’d lost an angus and her hybrid buffalo calf in birth. We’d had a pony and two dogs run over on the highway. A carful of us on our way to Sunday church ran over a kitten in the turn-around and its guts came out. I’d bottle-fed a calf in the mud cellar, a calf that I’d pulled from two foot deep cold manure in the barnyard. I’ll never forget his wheezing. He died. I’ll never forget my sister galloping full speed to our house, jumping down, running inside crying, and announcing to us that our little pony (either mom Rusty or daughter Stormy) had just that minute been struck and killed by a semi on Highway 212. Ope, I hope it wasn’t one of our three dogs, because two of them got killed out there. Our unbonded Ginger ran off. If so, I hope my sister will correct me. But our pony did get killed out there, too.

I’ve seen a lot of birth, too. Mostly, cow-calf operation type births, a quick herd builder, where you buy pregnant heifers, keep them in sight when they are close to term, you watch her behind for fullness and softening, then you assist in clearing the calf’s nose and mouth when it pours out of her. Or you tie a rope and pull it out of her. I’ve spied on our buffalo during birth. They’re weird and private. They circled the heifer, as is their custom, to protect her from wolves. But they caught my smell and stampeded after me until I ran through a gate, hooked around, and ran for the trees. I would have been dead meat, they are so fast.

Anyway, farm live is done, antique. Buffalo, horses, chickens, and cattle, my dad’s crazy aspiration to relive his youth in Wisconsin, are long gone from that property whose confines were a lonesome bullseye west of Minneapolis, and the windy sky a cirrus panorama in our lives.

Cocky strutted off down the gravel driveway, past the broken oak tree, with a butt infection and the pull tab of an open pop can hanging on one ankle. Always looking behind, but walking ahead, zigzag.

Lucky guy, Cocky Locky.

Here is Emily Zanotti’s farm piece about a chicken. It’s so good.

Here is my friend, Jenna Stocker’s latest Substack post. Her work is sublime.